Across Georgia, dozens of towns and cities large and small have turned to wall-size, outdoor murals to tell their communities’ stories, enhance civic pride and draw visitors. More murals are on the way as urban leaders realize the value of outdoor art to help make streets, parks and other public spaces more colorful, walkable and welcoming.

The Georgia Mural Trail project, for instance, aims to paint 50 murals in 50 cities under 10,000 people in five years across the state. “Our goal is to get other artists, organizations and sponsors on board to help with the painting, funding and marketing of the trail,” said Hapeville-based artist John Christian, who started the project.

For the talented mural artists, their canvases mostly are billboard-size walls of downtown buildings, schools, community centers and other structures. The murals are carefully planned and commissioned by businesses, organizations and local governments—as opposed to graffiti, defined as “writing or drawings scribbled, scratched, or sprayed illicitly on a surface in a public place.”

Lakeland v. Colquitt

In my Georgia travels, I seek out murals. In particular, two cities have become famous for their outdoor paintings—Lakeland in Lanier County and Colquitt in Miller County—both deep in South Georgia.

In December 2005, during a celebrated visit to Lakeland, then-Gov. Sonny Purdue officially proclaimed the city of some 3,400 people and 30 murals as “Georgia’s Historic Mural City.” That notion, however, did not sit well with folks some 100 miles west in Colquitt (pop. 2,000, 16 murals). Not to be outdone, Colquitt’s leadership persuaded the 2006 General Assembly to declare their community as “Georgia’s First Mural City.”

Some called the friendly feud the “Battle of the Murals.” For both cities, however, the official designations are well-deserved.

The largest mural in the country

Colquitt even has a national mural boast—home to what is said to be the largest mural in the United States. Popularly known as “The Peanut Farmer,” the mural is painted on the sides of the 100-foot tall silo of the Birdsong Peanuts Company, which looms over down town and depicts a farmer inspecting his crop before harvest.

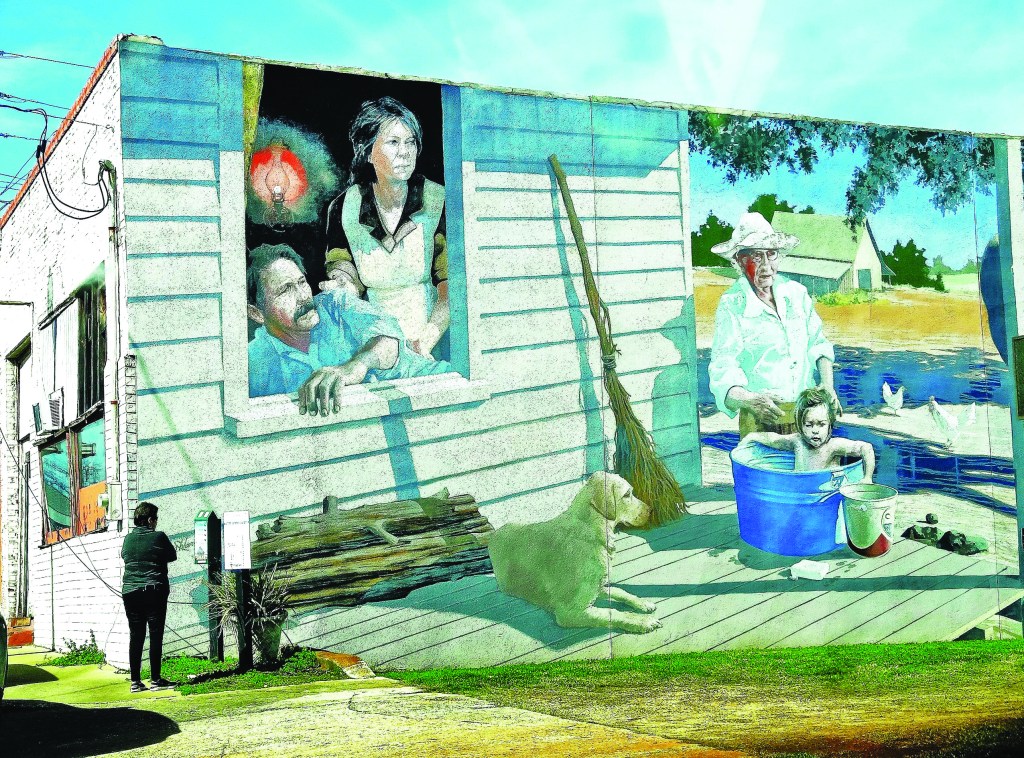

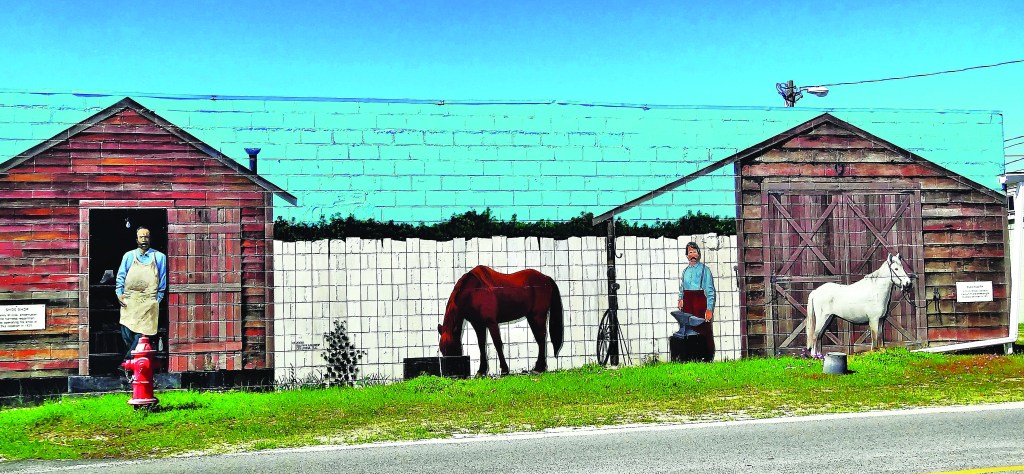

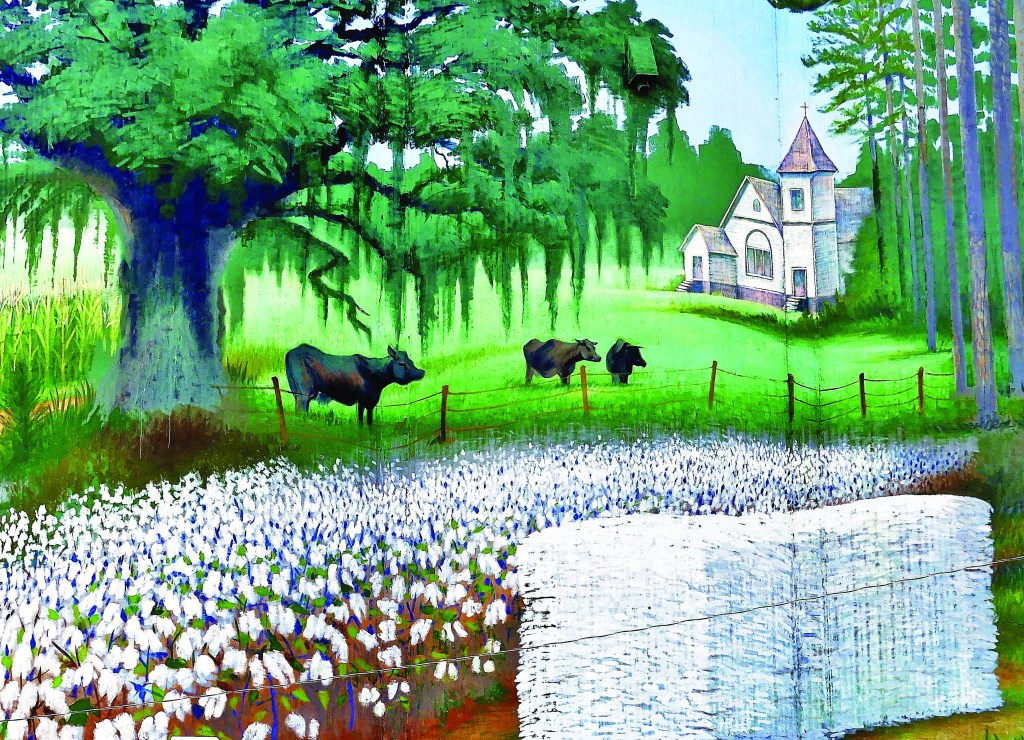

Colquitt’s murals are part of a project known as the Millennium Murals, started in 1999 with funding from the National Endowment of the Arts. Each mural represents local folk life in the area. Some depict real people who lived and worked there; some are based on the stories told through Colquitt’s highly acclaimed theatrical production, Swamp Gravy, Georgia’s official Folk Life Play,

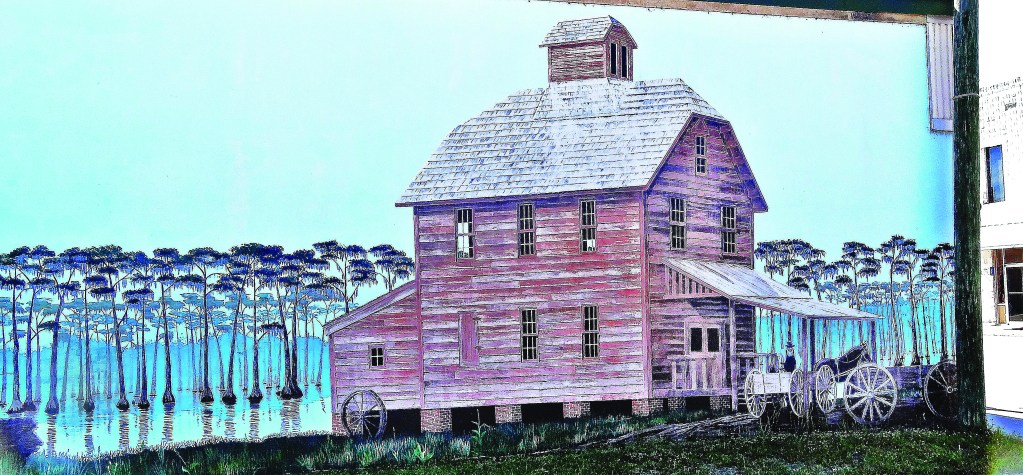

Lakeland’s breathtaking murals center around one day, Sept. 15, 1925, when the town’s name officially changed from Milltown to Lakeland to reflect its proximity to scenic Banks Lake. Lakeland’s Milltown Murals vividly reflect a simpler way of life in a south-central Georgia town in the 1920s.

John Fitton, director of the Lakeland-Lanier County Chamber of Commerce, said he never tires of strolling around Lakeland and seeing the murals. “The people in them are now like family,” he told me. “It helps me stay connected to the past.”